Tom Weisz: A Patient Partner Who Kept Us Moving from Knowing to Doing

For nearly a decade with Diabetes Action Canada, Tom helped push foot care forward, asked the hard questions, and reminded us that real impact takes teamwork and persistence. As he retires from the Network, Tom sat down with DAC Executive Director Tracy McQuire to reflect on what he’s learned, what he’s helped shape, and the questions he’s carrying into this next chapter.

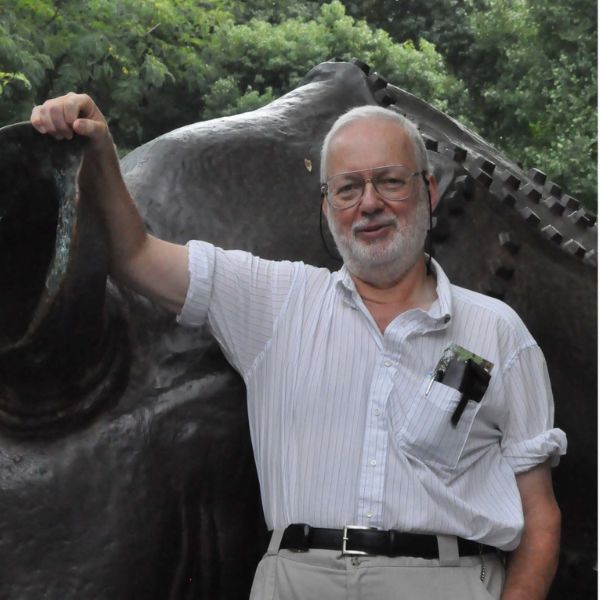

Some people change a network with a big, sweeping idea. Tom Weisz changed ours by doing something quieter and often harder: showing up, staying curious, and refusing to let important work stall at “good conversation.”

Tom has been part of Diabetes Action Canada (DAC) since the early days. As he steps back from his formal Patient Partner role, we wanted to pause and say thank you not just for what he contributed, but also for how he contributed: with humour, honesty, and a steady insistence that knowledge only matters if it leads to action.

“Knowing without acting is effectively meaningless.” – Tom Weisz

What brought Tom to DAC

Tom did not come to patient partnership looking for a title. He came because someone challenged him not to waste what he had learned.

Just before he retired from his professional career as a podiatrist, a nurse colleague offered a piece of advice Tom still carries: do not stop contributing just because you are retiring. Around that same time, he was publishing and presenting on diabetic foot care work that put him in rooms where policy, practice, and lived experience collided.

One moment still makes him laugh: attending a conference, hearing a speaker reference “a small article that sums it up nicely,” and realizing the article on the screen was his. That speaker was Dr. Charles de Mestral, and it sparked a connection that brought Tom into DAC’s growing community.

“Next thing I know, I was involved in this, that, and the other,” Tom said — a classic understatement.

A champion for foot care and the long game of change

Many people across DAC know Tom through his contributions to foot care and lower limb preservation work. He has helped keep the reality of complications on the agenda; not to scare people, but to be clear-eyed about what prevention can protect.

Tom’s approach is direct, grounded, and shaped by experience. He understands how easily diabetes complications can be minimized until they become urgent and how hard it can be to shift systems before that moment arrives.

But he also understands something else: change is rarely a single event. It is often a slow build.

Tom described it like this: you can chip away for a long time and only see tiny changes — until one day, you hit the right point and a whole section finally moves. For anyone who has worked on policy, funding, or practice change, the analogy lands.

A learner by nature — and a connector by instinct

If you ask Tom what stood out most over the years, he does not start with accomplishments. He starts with people.

“Without fail,” he said, “there’s not an individual who I’ve come across… that I wouldn’t love to break bread with.”

Tom talked about how much he learned through DAC, not only about different types of diabetes, but about broader realities that shape health outcomes: the health inequities experienced by Indigenous Peoples, stigma, access, and the everyday barriers people face navigating care. His default setting is curiosity, and he treats “I don’t know” as an invitation, not a weakness.

“Everybody knows something you don’t know.”

That mindset made him a steady presence in patient partnership spaces where DAC teams bring ideas, tools, and drafts to be tested, not just for whether they are “good,” but whether they will actually work in real life.

The role Tom played: the question-asker who sharpened the work

Tom often described himself as not being part of the “organizational” side. He was not seeking to run processes. Instead, he was the person you brought something to when you needed it pressure-tested.

As a member of the DAC Collective Patient Circle, he valued this group as a safe place for people to disagree, to speak up, and to improve ideas early before they became finished products that were harder to change.

And he noticed something important: over time, people got more comfortable naming what didn’t work, not just what did.

That ability to surface what is missing, to ask the question that unlocks the next step, is one of Tom’s gifts. It shaped projects in visible and invisible ways, including DAC’s Research to Action Fellowship (where his feedback helped strengthen the program design) as well as the Patient Partner Recruitment process.

Tom’s “secret sauce” for patient partnership

When asked what makes patient engagement work, Tom did not give a slogan. He gave a practical recipe:

- Be clear on your target — know what you are actually trying to change.

- Do not insist on one route — there are “a bazillion ways” to get there.

- Do not “hear” the word no — expect it, and keep going anyway.

- Build up the team — you will not do it alone.

He compared it to sport: a good play only works when everyone does his or her part. The “stars” might get the spotlight, but the outcome depends on the whole team.

And he named the truth that patient partners often know best: this work takes time and sometimes progress arrives in bursts after long stretches of slow effort.

Life shifts — and why Tom is stepping back (for now)

Tom is retiring from his formal DAC role due to a shift in health priorities. He shared openly that he and his wife have been navigating long COVID, and that energy is now the limiting factor, not commitment.

As Tom steps back, he is not stepping away from questions that matter. He is turning his attention to a growing and complicated intersection: diabetes and long COVID. For him, the tension is practical—diabetes care often emphasizes exercise, while long COVID can make physical activity unpredictable or impossible. It is a gap he is actively trying to understand, and one he hopes the research community will take seriously and study in depth.

“As someone with diabetes, you’re always told exercise matters for blood glucose. But with long COVID not everyone can exercise. That’s where I’m looking now: what does good care look like when diabetes guidance and long COVID realities don’t line up?”

For Tom, the question is ultimately clinical: what can physicians actually offer; what can they say or do when a person is living with both diabetes and long COVID, and the usual tools (like exercise) don’t apply? He’s hopeful for practical guidance that improves day-to-day health and he is candid about the urgency: he doesn’t want it to take 15 years for emerging evidence to reach the clinic door.

Even as he steps back, Tom’s identity as a contributor has not changed. He still reads widely, follows emerging evidence, and shares articles when something feels important, especially when it connects diabetes with broader health issues.

And while he’s stepping away from committee responsibilities, his message to DAC was simple: he’ll miss the people, and he hopes to re-engage when he can.

Thank you, Tom

Tom, thank you for nearly a decade of partnership, for helping elevate foot care and prevention, for asking the questions that made our work better, and for reminding all of us that progress is only progress when it turns into action.

We are grateful — and we’re keeping a seat open for you.

Calls to action

- Interested in becoming a DAC Patient Partner? Sign-up here

- Learn more about DAC’s Patient Engagement approach and programs.

- Stay connected: sign up for updates here